Elizabeth Blackwell was born in Bristol, United Kingdom, in 1821. Her father, Samuel Blackwell, was a sugar refiner, a Quaker, and an anti-slavery activist. As a prominent supporter of social reforms, Elizabeth’s father pushed for the education of all of his children, including his daughters. This was especially progressive during this time, because women had a very limited social role in the early 1800s. A woman was expected to focus on being a mother, a housekeeper, and (in the lower-class families) a worker. Women were not allowed to attend college, could not file for divorce, and had very few rights. Often, the treatment of women in this time period is compared to slavery. A woman was expected to be submissive to her father and her brothers, and later in life, her husband and sons. However, thanks to Elizabeth Blackwell’s accomplishments, the way the United States and much of the Europe viewed women was changed forever.

In 1832, the Blackwell family moved to the United States. Shortly after the move, Elizabeth’s father died, leaving the family in a financial crisis. To try to help the family raise money to survive, Elizabeth and her sisters set up a school. A few years later, one of Elizabeth’s good friends became terminally ill, and often complained that a female physician would be more considerate than her male counterparts. Her friend’s complaints, and later, her death, spurred Elizabeth to become a physician. Another reason Elizabeth was so focused on this career path was the fact that she wanted to create a barrier between herself and marriage. She felt that this high-stress, time-consuming profession would be the excellent excuse to avoid it. A quote, found in her diary, shows that she found love a trivial thing:

“I must have something to engross my thoughts, some object in life which will fill this vacuum and prevent this sad wearing away of the heart.”

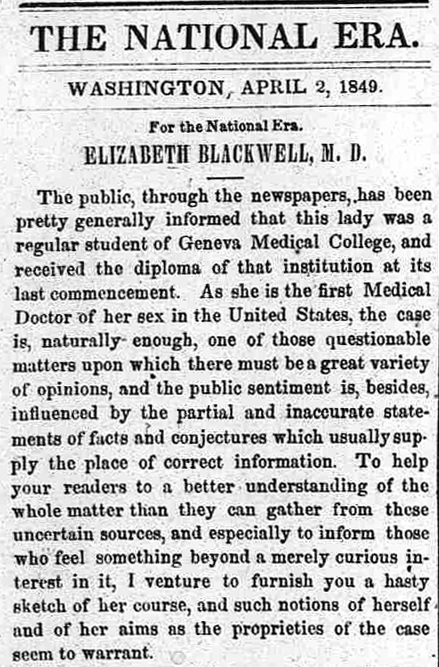

Samuel Blackwell, an active social reformer, made sure his daughters, as well as his sons, received an education. After finishing high school, Elizabeth applied to many colleges. When none of them accepted her on account of her gender, she began to apply to smaller, rural colleges, and eventually was accepted to Geneva Medical College (in New York). Although she was severely discriminated against (some of her professors forced her to sit separately from her fellow students, and the students often pulled practical jokes on her), she thrived at Geneva. Graduating top of her class in 1849, she became the first woman in American to earn a medical degree. This news spread quickly, and the editor of a newspaper, The National Era, wrote a long article about her in which he stated:

“She is one of those who cannot be hedged up, or turned aside, or defeated.”

The National Era, Apr. 2, 1849

Courtesy Library of Congress. Source.

The National Era, Apr. 2, 1849

Courtesy Library of Congress. Source.

She later moved to Paris, where she studied midwifery in La Maternité. She contracted purulent ophthalmia, causing her to lose sight in one of her eyes, dashing her dreams to become a surgeon. Elizabeth was not very disappointed however, for she knew she could continue to help people and earn recognition for women physicians.

In 1857, she returned to the United States, where she, her sister (Emily) and Dr. Marie Zakrzewska established the New York Infirmary for Women and Children. She continued to periodically visit the U.K., trying to raise money to establish a parallel institution there. In 1859, a huge milestone for her and women doctors everywhere, Elizabeth was officially recognized as a doctor by the British General Medical Council. This gave her more credibility, and her number of patients greatly increased.

During the Civil War (1861-1865), Elizabeth and her sister, Emily, supported the medical unit of the Union army, by training nurses for their hospitals. During this time, Elizabeth, as well as many other physicians, most likely used a saddlebag (often made of leather) to easily store and carry their medicines. A similar bag can be found in the Luce Center, containing medicinal containers, with handwritten labels that read “Buchu”, “Geranium”, and “White Rock.” Elizabeth definitely used similar medications when caring for her patients.

In November of 1868, Elizabeth had raised enough funds to establish a medical college for women in the U.S. Leaving her sister in charge of the school, she moved back to England in 1869, and founded the National Health Society (1871), which stressed the need for personal hygiene, especially because male physicians had spread diseases by not washing their hands between patients. In 1874, Elizabeth Blackwell, Sophia Jex-Blake, and Elizabeth Garret Anderson (two other British physicians, established the London School of Medicine for Women. By 1875, Elizabeth was appointed professor in gynecology.

In 1876, the legislation to allow women to earn medical degrees was passed, thanks to Elizabeth’s participation in social reform movements. She also supported movements such as: moral reform, sexual purity, hygiene, preventative medicine, sanitation, family planning, women's suffrage, the abolition of prostitution and white slavery, morality in government, and the liberalisation of Victorian prudery.

After retiring, Elizabeth mainly focused on reform movements and her autobiography, Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical Profession to Women, which was published in 1895.

Elizabeth Blackwell died in Hastings, England, in 1910, and her death was mourned by many women. Blackwell is an incredibly strong and prominent figure in Women’s History. She was the first woman to earn a medical degree from a college in the United States, she was the first woman to be registered as a doctor in the U.K., and she founded many institutions, and helped hundreds and thousands of people. She inspired many women to pursue careers in medicine, and thanks to her efforts, by 1881 there were 25 registered female doctors, and by 1911, that number had risen to 495. Blackwell’s incredible work continues to inspire many women today, as it did in the 19th century, and reform efforts contributed to many of the rights that are freely available to us today.