The fruit of her educational labor landed her in the National Central University in Nanjing in 1934, during which many breakthroughs in physics arose. Shadowing a professor who had worked with Ms. Curie was another golden opportunity for the young Wu. In 1936, she traveled to America and studied at UC Berkeley, since limited education opportunities in China nevertheless prevented Wu from reaching her full potential. Wu never saw her parents again, but when she immigrated to America, she helped with the American war effort after hearing that China was invaded by Japan.

Legacy and Accomplishments

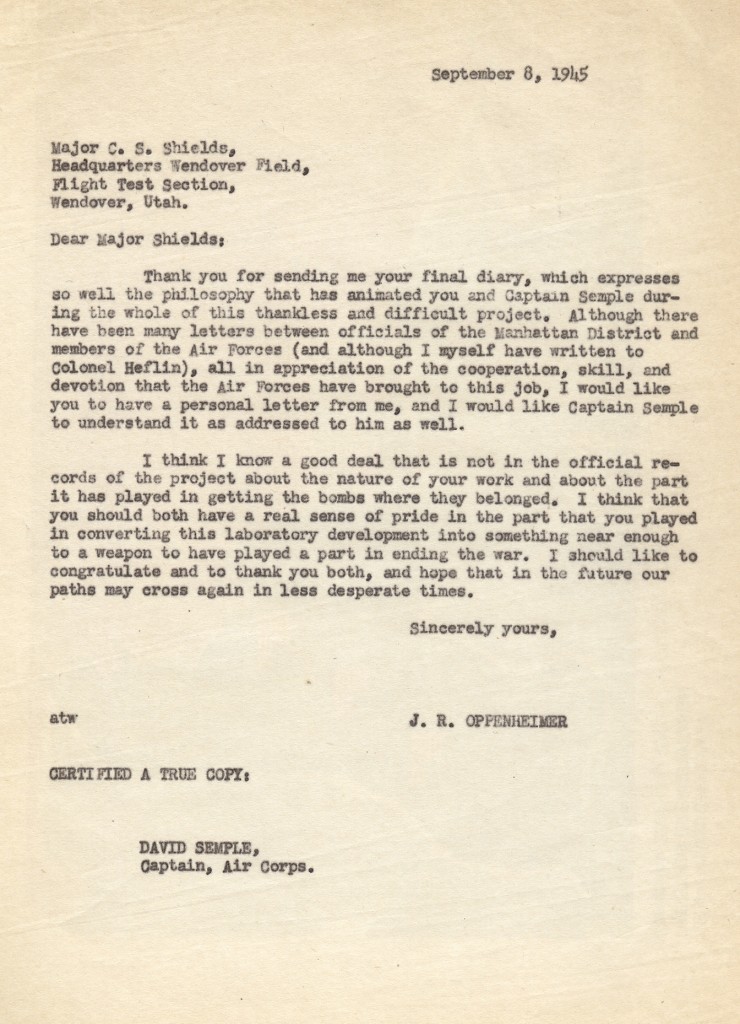

Chien-Shiung Wu with fellow research scientists Y.K. Lee and L.W. Mo at Columbia University. Archived by the Smithsonian Institution. Photo taken on 3/20/1963.

Years later at Columbia, her cutting edge research attracted the attention of Tsung-Dao Lee and Chen-Ning Yang — two physicists who had a query regarding the law of the conservation of parity. The two had theorized that parity (the status quo as was theorized) might not exist with beta decay, but there was no more accurate researcher than Wu who could help affirm or negate their doubts. In other words, Wu had to prove that beta particles were asymmetrically emitted by cobalt nuclei. Wu used the nuclei to illustrate how the same number of electrons weren’t thrown around after the nuclei broke down, showing how subatomic interactions disprove the “self-evident” principle. Her discovery was recognized in the New York Times. In spite of that, she was never given credit on par to the resultant Nobel Prize winners of Lee and Yang, as she had worked along them side by side but was deemed inferior due to sexist norms. Nonetheless, Wu wasn’t bogged down and continued to challenge society’s own “self-evident” principles that boxed her. She broke down preconstructed barriers when she confirmed the resultant Nobel Prize winner Enrico Fermi’s theory of beta decay.

She was the first woman elected as President of the American Physical Society. She wrote a book on beta decay that is still relevant today. A charismatic woman, she was once deemed by her colleagues to be even wittier than Curie herself. Her beta decay experiment establishing the non preservation of parity in weak force particle reactions set the precedent notion of learning to challenge authorities and be daring enough to think outside of the box when it came to any innovation, scientific or not. She advanced society’s knowledge about blood and sickle cell anemia, and she was honored the National Medal of Science and Wolf Prize in Physics. Wu was truly extraordinary, both as a changemaker and an influential thinker. She helped disabuse society of preconceived notions regarding women, and she benefited science in numerous ways. She also used her platform to advocate for women in STEM. As she had said, "I wonder whether the tiny atoms and nuclei, or the mathematical symbols, or the DNA molecules have any preference for either masculine or feminine treatment.” It is because of her that women in science have a growing amount of role models, for many have been inspired by her. Her story must be passed on, so future “Madame Curie’s” or even, say, “Madame Wu’s” may emerge.