Biography

Fredericka “Marm” Mandelbaum was born Friederike Henriette Auguste Weisener in Hanover, Prussia in 1827. She married Wolf Israel Mandelbaum and immigrated to the New York City at the age of 23. They lived in Kleindeutschland (Little Germany) in the Lower East Side. The Mandelbaums were a family of six, with two sons and two daughters, and though they tried to provide for their families by peddling wares, the meager income was not enough.

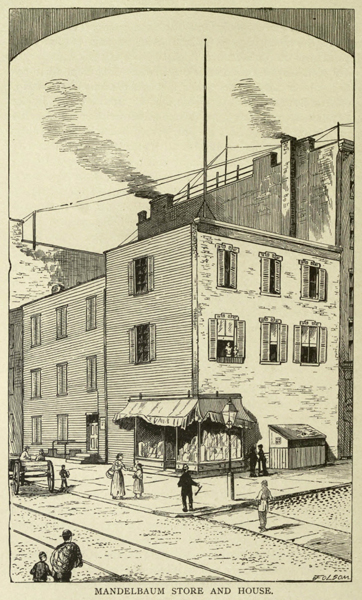

In the Panic of 1857, hundreds of businesses failed, banks closed and tens of thousands of people lost their jobs. Children, no longer being provided for, began to linger in the streets. Many began to pickpocket. Mandelbaum became a sort of mentor for these children. She bought the wares they stole and sold them for a profit. In 1865, she opened a dry goods store at Clinton and Rivington Streets, as a front for fencing goods.

Mother Mandelbaum’s storefront and house, from Recollections of a New York Chief of Police by George W. Walling (New York: Caxton Book Concern, 1887)

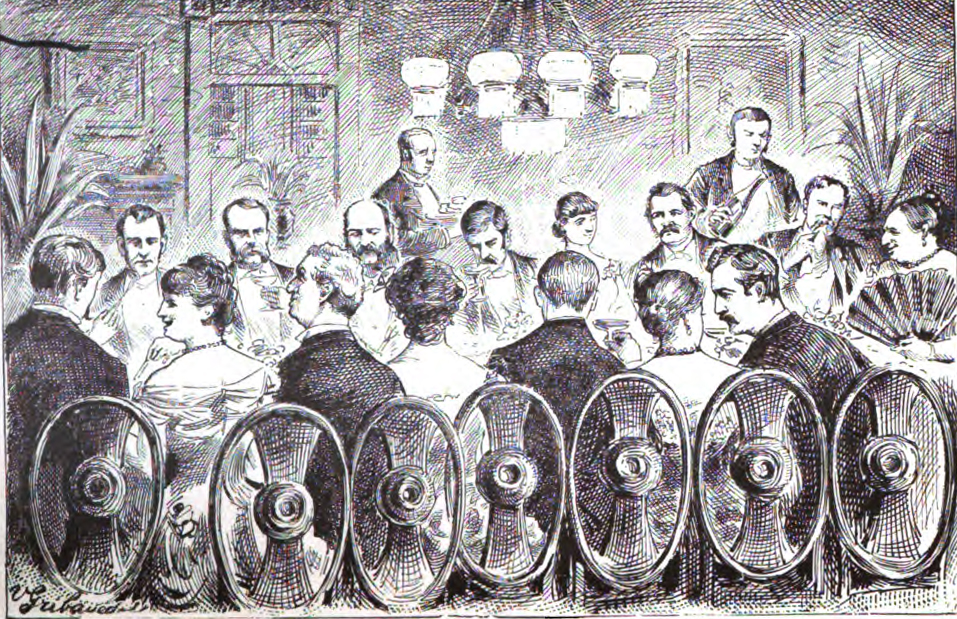

As her empire began to grow, she created a network of associates: crooked cops and judges, engravers to doctor jewelry, hansom cab drivers for quick getaways, and the defense attorneys Big Bill Howe and Little Abe Hummell. She regularly threw big parties, with guests such as prominent criminals, police, judges, and politicians.

William Howe and Abraham Hummel, from Danger! A True History of a Great City’s Wile and Temptations by William Howe and Abraham Hummel (Buffalo: The Courier Company, 1886)

An illustration by Valerian Gribayedoff of a typical Marm Mandelbaum dinner party, from Recollections of a New York Chief of Police (1887) by George W. Walling

When conducting business, she always took Herman Stoude and one of her sons or daughters, to keep watch for detectives. Typically, Mandelbaum offered one-fifth of the wholesale price. After the transaction, Stoude would bring the goods to one of her many warehouses or to her home, where she had a series of hiding places. Her favorite was a chimney with a false back, behind which a dumbwaiter could be raised or lowered with the pull of a lever. If something were to occur, she could simply drop it out of sight.

Diagram of Mandelbaum’s false chimney from Why Crime Does Not Pay by Sophie Lyons (New York: J.S. Ogilvie Publishing Co., 1913)

Mandelbaum opened a school on Grand Street where children could learn from professional pickpockets and thieves. More advanced students could learn burglary, safe blowing, confidence schemes, and blackmail. The school thrived, until the son of a prominent police official enrolled, which even Mandelbaum deemed too risky and preemptively closed the school, for fear of detection by the police.

In October, 1878, Mandelbaum financed New York’s first great bank robbery, the Manhattan Savings Institution.

Detective Gustave Frank, using the alias Stein, took lessons from a silk merchant on quality and pricing; after an introduction from a supposedly loyal client, Marm began conducting business with him. When the police raided her various warehouses, they discovered the silk Stein had sold her and enough stolen goods to put her away for life.

Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency letterhead, from The Spy of the Rebellion, The New-York Historical Society.

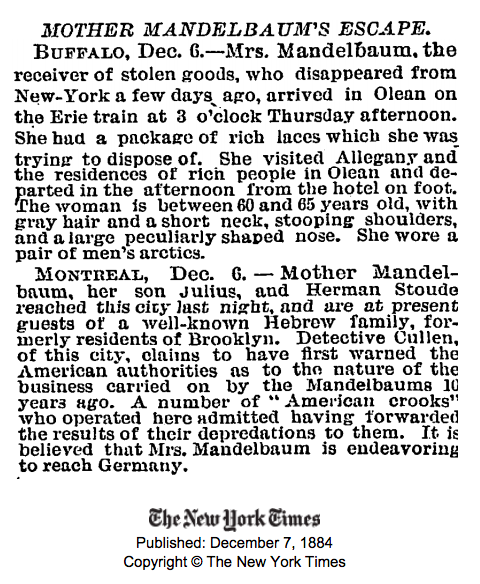

On December 5, Marm jumped bail and fled to Hamilton, Ontario, where she lived as a seemingly law-abiding citizen who donated to charities, joined the Anshe Sholem Hebrew Congregation, and worked long hours in her hat shop.

This New York Times article, published in the December 7th, 1884 issue, records the escape of Mandelbaum to Canada.

In this cover of Puck, June 17, 1885 issue, Mandelbaum is depicted as “Canada” effectively serving as a “fence” protecting criminals from American law enforcement. Canada as "Mother Mandelbaum", by Joseph Ferdinand Keppler, 1885. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Though she is recorded to have died on August 27th, 1894, there were theories that she was not in fact dead. Instead, some said had loaded her coffin with stones, to eliminate any search or monitoring of her.